Grayshott: Sally Grainger is a Roman food historian and archaeologist, a scholars’ scholar whose decades of experimentation and genre-breaking research shattered hundreds of years of misconceptions about Roman food and Roman cooking. Her revolutionary methodology is simple: recreate a Roman kitchen and figure out how to make food that tasted nice, which, in turn, allows for a more accurate translation. As she explained in her introduction to Roman Recipes for Modern Cooks, a new cookbook illustrated by Joana Avillez: ‘It was historians and scholars, rather than cooks, who largely dealt with the Latin and Greek recipes in the past’.

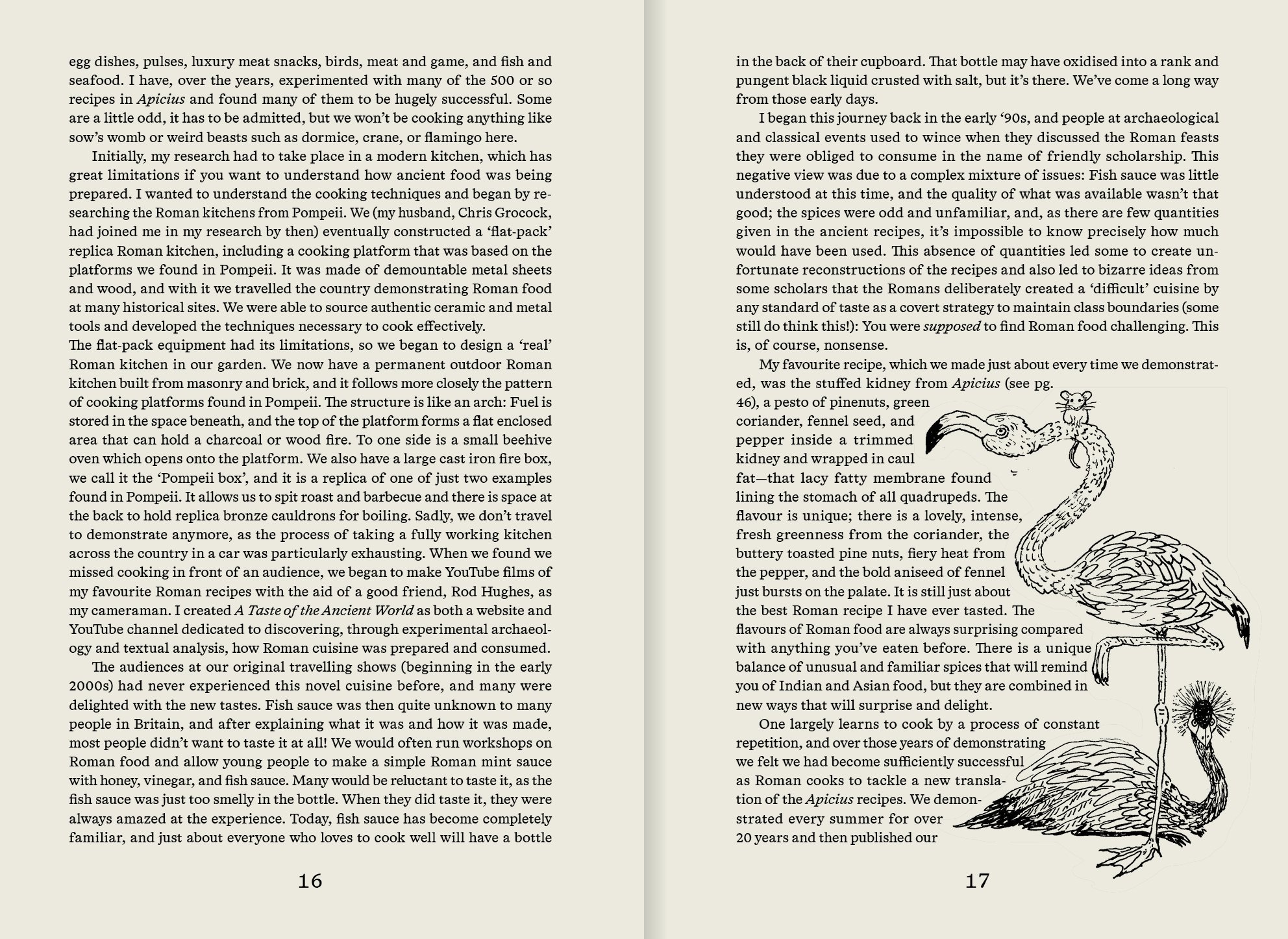

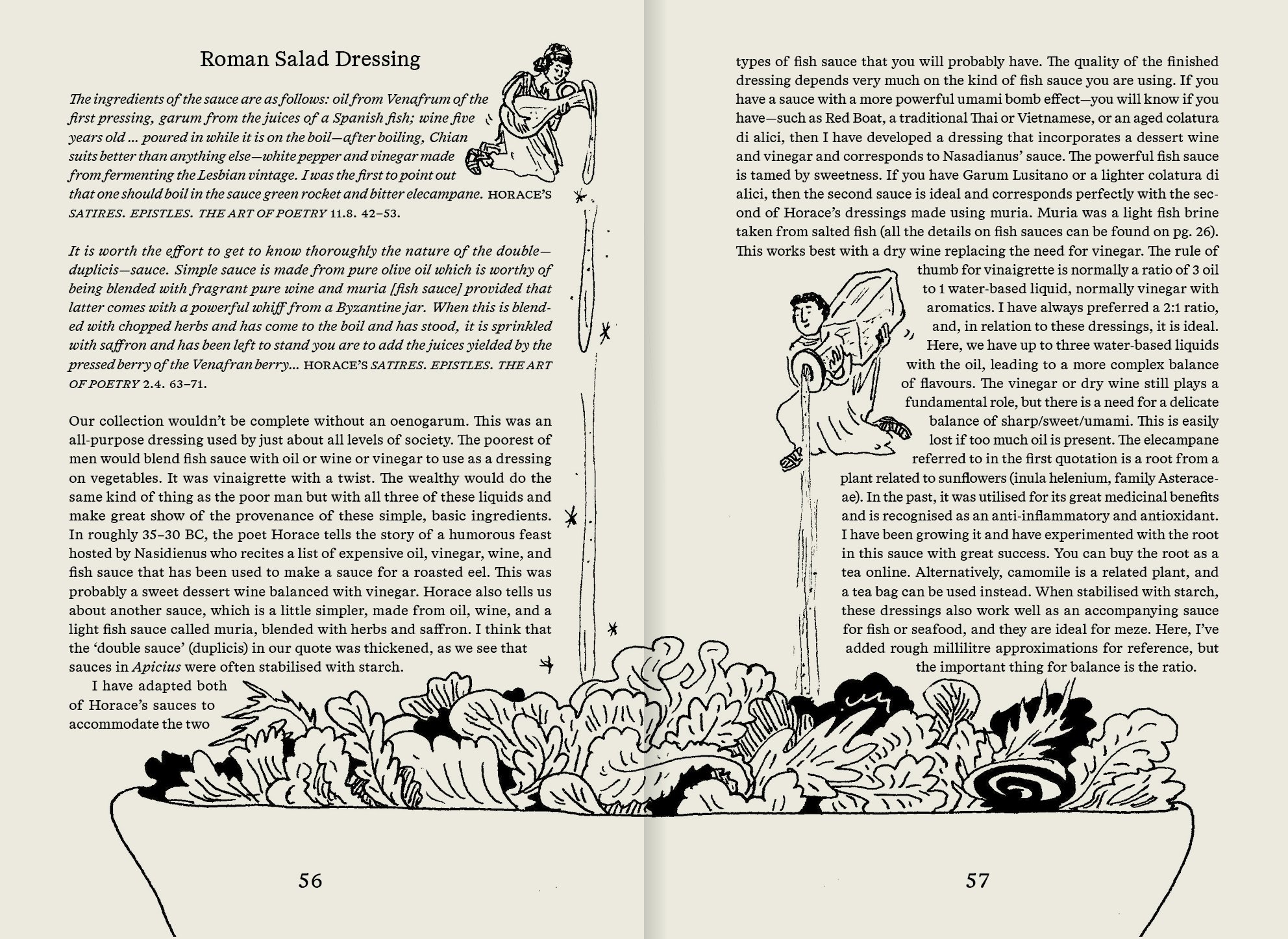

While many famous ancient cookery books were attributed to nobles like Apicius Marcus Gavius from the first century AD, recipes were most likely dictated by cooks (for cooks) who did not feel the need to explain the obvious. Therefore, when ancient recipes were interpreted by scholars, disastrous attempts led to a belief that wealthy Romans used nearly inedible dishes as a way of preserving class boundaries: ‘This is, of course, nonsense’, maintains Sally, who made it her mission to make Roman recipes accessible.

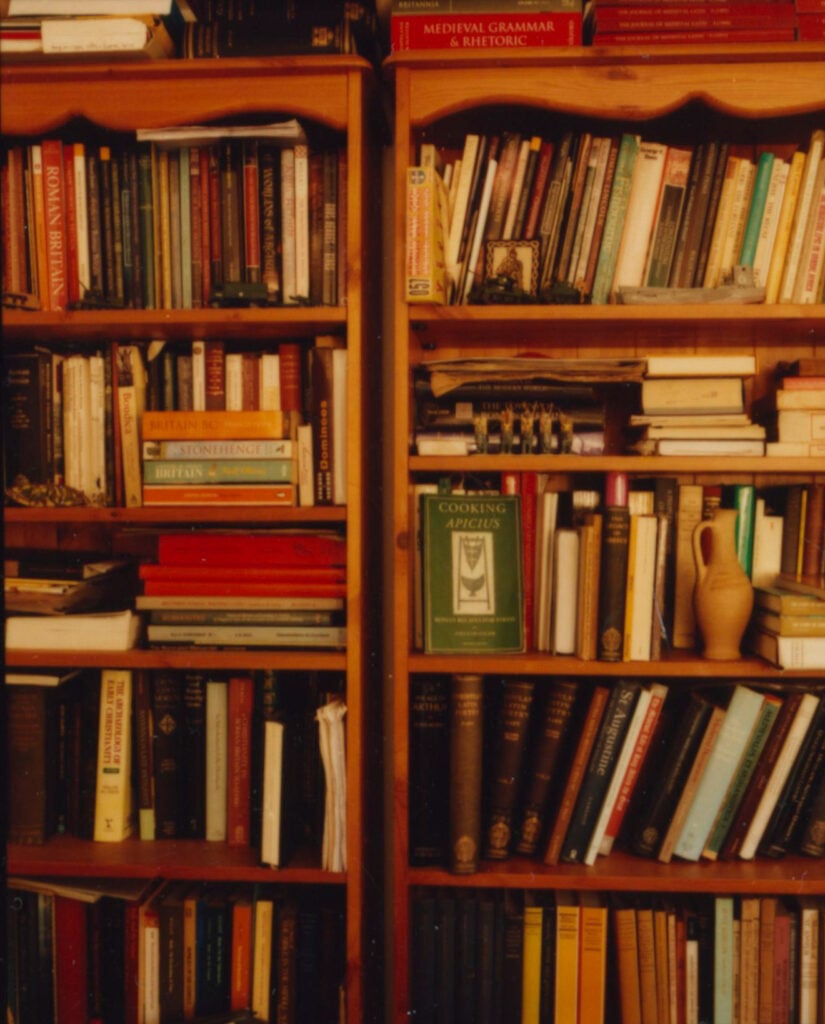

After years as a pastry chef, Sally entered into a career in classics as a mature student, giving her unparalleled insight when presented with Greek and Roman recipes which had defeated translators. Beginning on a whim to elevate a university toga party, her Roman dinners slowly built up her reputation for authentic scholarship, leading to designing dishes for the likes of the British Museum (for their Pompeii exhibition), the Museum of London, and being called in as an expert on documentaries like Pompeii with Michael Buerk. In the midst of all this, Sally published several books: The Classical Cookbook (a co-translation with Andrew Dalby), Apicius: critical edition with introduction and English translation (with her husband, Christopher Grocock, a medieval Latinist), Cooking Apicius, and The Story of Garum: Fermented Fish Sauce and Salted Fish in the Ancient World, as well as a blog and YouTube series called ‘A Taste of the Ancient World’.

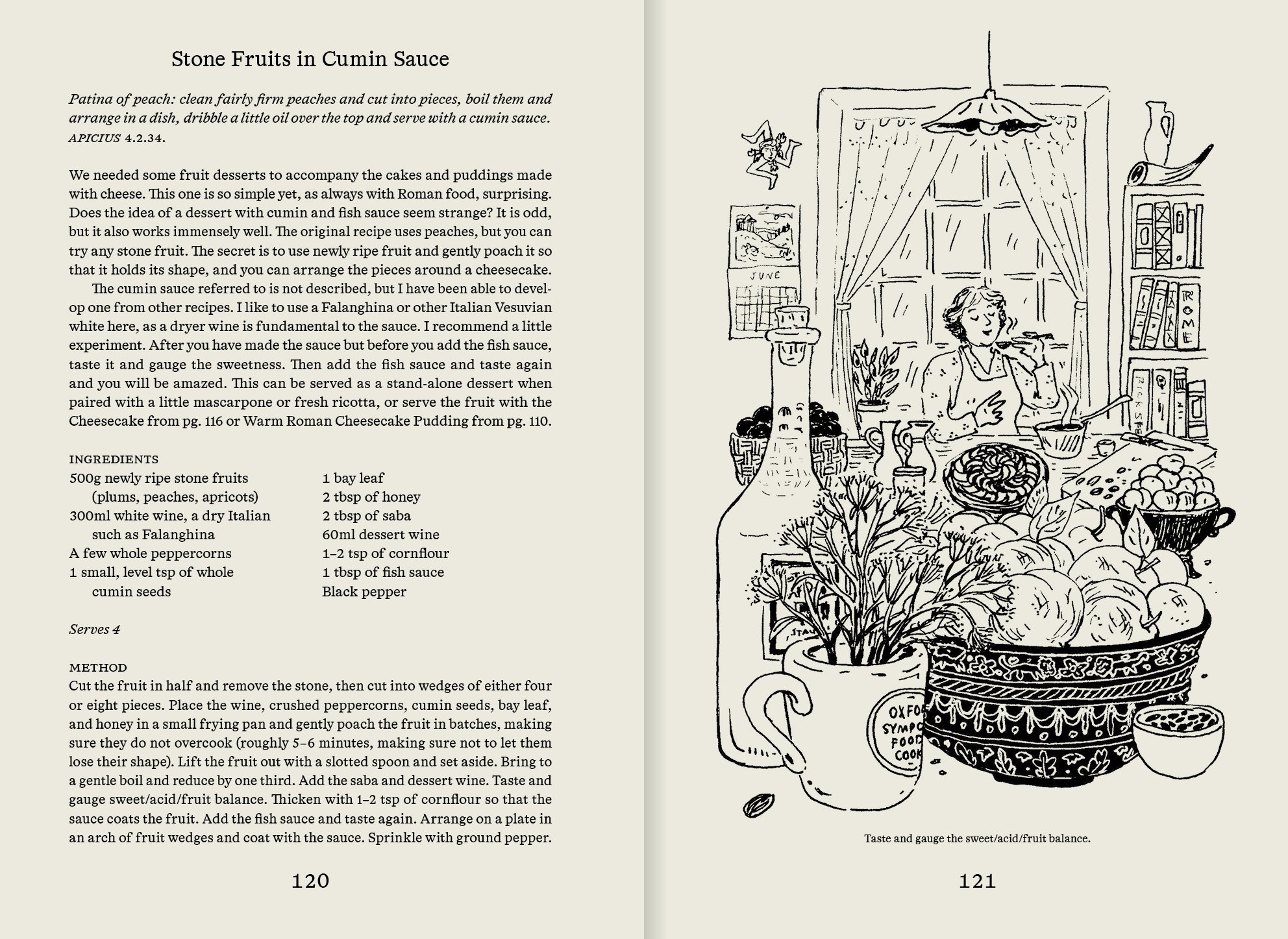

As an editor, working on Roman Recipes for Modern Cooks sent me tumbling down an incredible rabbit hole of her books, literary references, and videos. Sally exudes ease and a palpable enthusiasm as she moves around her wares, quick to smile, quick to laugh, and quick to offer her neighbour turned cameraman, Rod Hughes, a bite of Roman burger or Roman cheesecake. Inspired by her hands-on translation and archaeological practice, I brought the manuscript into my home kitchen to try ‘Salsa Verde with Mullet’. The first attempt was delicious, though I couldn’t find dill seeds or celery seeds in Barcelona. ‘Oh, those seeds were definitely needed to make the sauce successful’, she wrote via email. I tried again after sourcing the seeds, and Sally was right, of course.

close

close