Carnelian Bay: Exploits of physical grace and at times questionable sanity wedded to self-reliant ambition and hard work are Craig Beck’s métier, a legacy still in the making at the slightly mellowed age of 78. Craig’s notoriety can be traced to his films, going back to arguably the world’s first ‘extreme’ ski movie, 1973’s 8mm Timepiece, followed by his 1975 opus, Daydreams, which brought him worldwide attention both from in and outside of the ski circuits. Self-financed, edited, and scored completely by Craig, it features the talents of such luminaries as his brother Greg, Dave Burnham, Chris Von Der Ahe, Brady Keresy, Pecos Welch, Earl Downing, and Mark and Tuck Rivard, among others. Highlighting the discipline’s avant-garde of the time, the skiing is, needless to say, amazing. But there’s plenty more than just 100-foot jumps off Squaw Valley’s Palisades; between manoeuvres and jump turns on 50-degree pitches, there’s also the sun, wind blowing flakes through the ether, and many serene, contemplative ‘daydream moments’.

It’s important to note that none of these people were paid. These were real ski bums in the best sense of the epithet, emblematic of a more innocent era before professionalisation and commodification became endemic in action sports. This cinematic endeavour showcases the fast-changing technological and artistic developments of the freestyle gestalt at its beginnings, when it was still unashamedly called ‘hot dogging’. Serious undertakings, yes, but without the overdetermined, self-referential, overly documented tawdriness so prevalent today.

As witness to, chronicler, and participant in this era of skiing, Craig has an unusually clear-eyed outlook on the ramifications of ‘progress’ vis-à-vis his close personal relationship to the sport’s inherent and frequently fatal dangers. Consequently, the sobering topic of early demises hovers over this exchange, evidence of Craig’s philosophical relationship to the extremely thin line between this side and the other. That said, he’s the opposite of gloomy or morbid; to the contrary, he is full of life and still stoked.

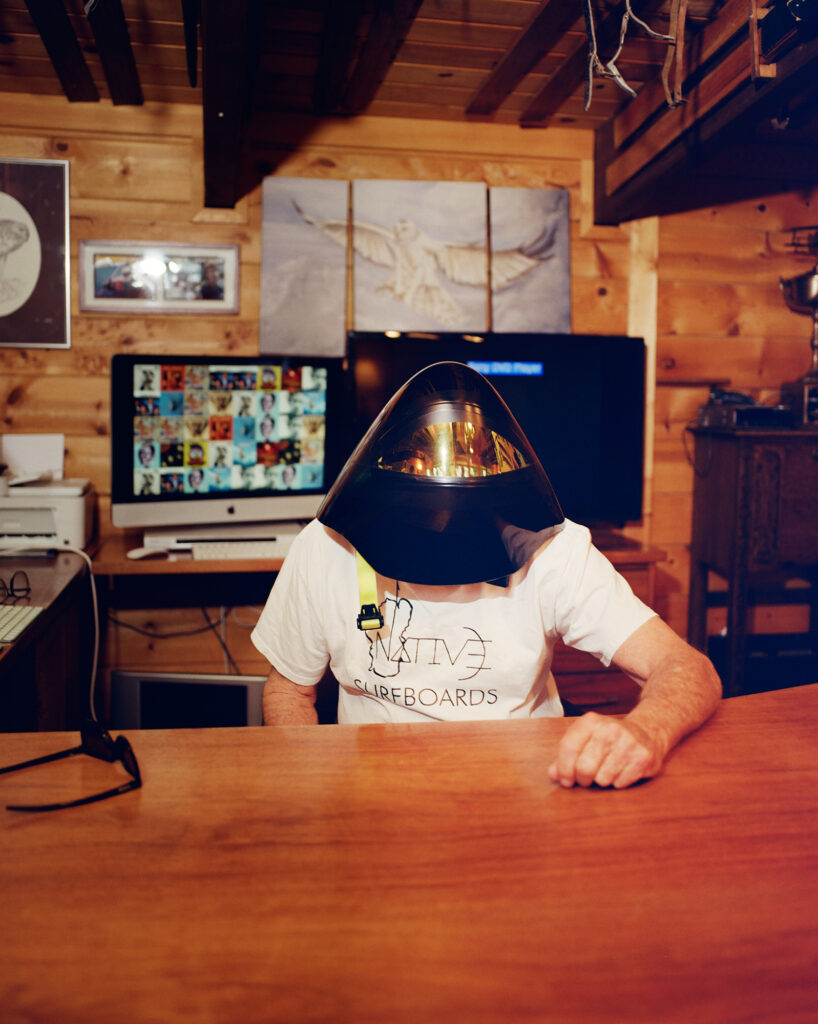

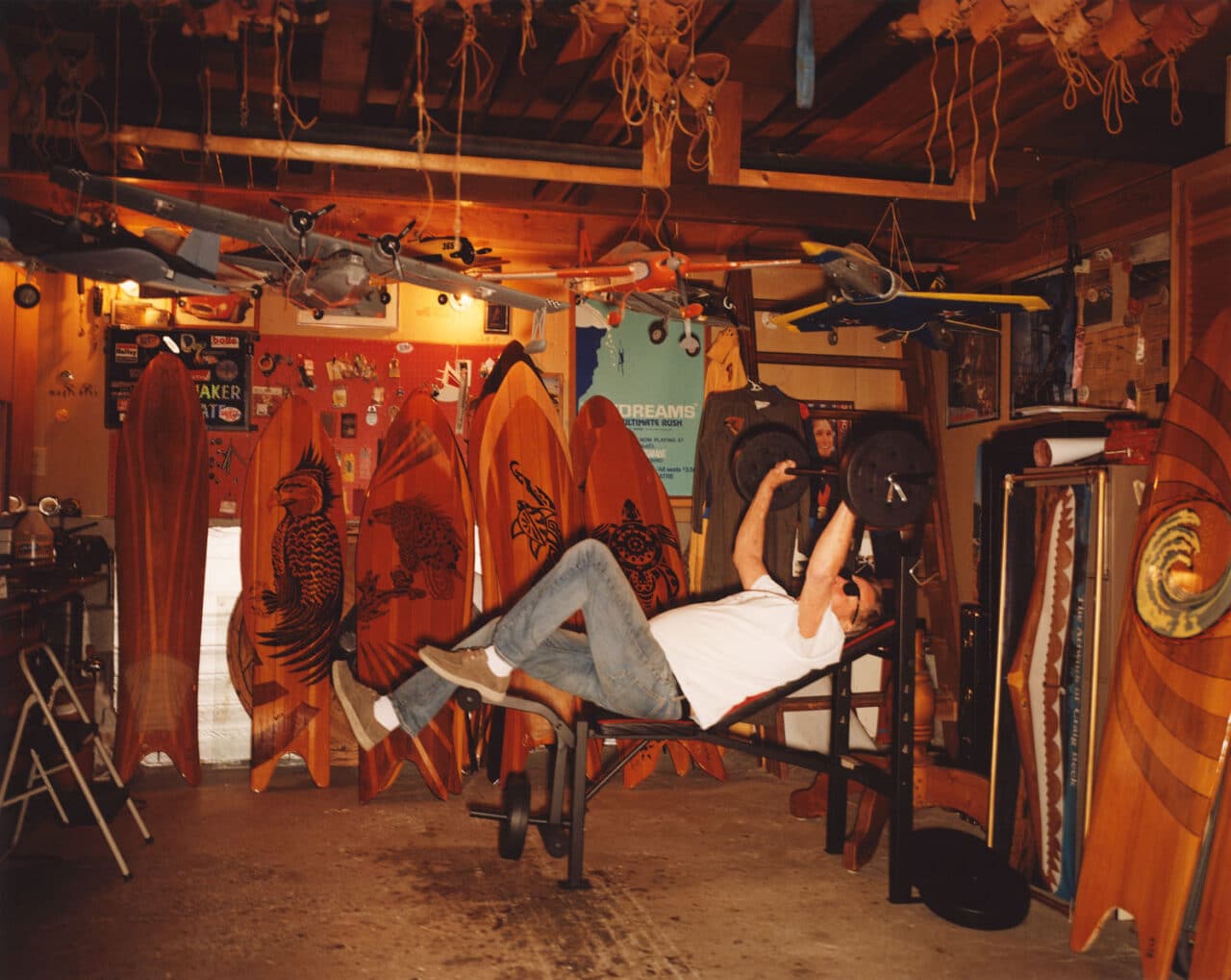

Through it all, Craig worked as a ski messenger at the 1960 Olympics, became an early hang gliding trailblazer, made more films, and also nurtured a long-running interest in 19th-century longboard ski racing and legendary Sierra Nevada mailman John Albert ‘Snowshoe’ Thompson. In more recent years, he’s committed to making and riding handcrafted lake surfboards. Surrounded by 19th-century skis, aerodynamic helmets, aeroplane models, and handwritten hang gliding flight logs in the upstairs office above Craig’s workshop, we screened Daydreams before embarking on this wide-ranging conversation. The at times awe-inspiring anecdotes and attendant answers are related here by a gifted raconteur who seamlessly mixes the gravitas of experience with an unbridled enthusiasm for recounting past adventures, combined with a keen view toward future undertakings.

close

close