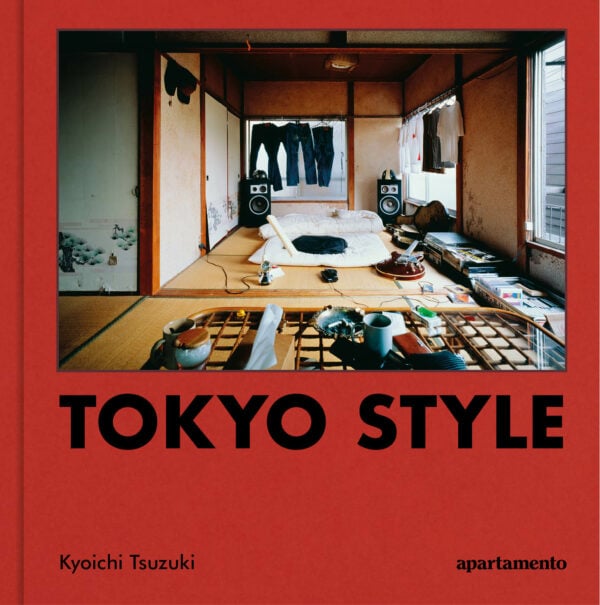

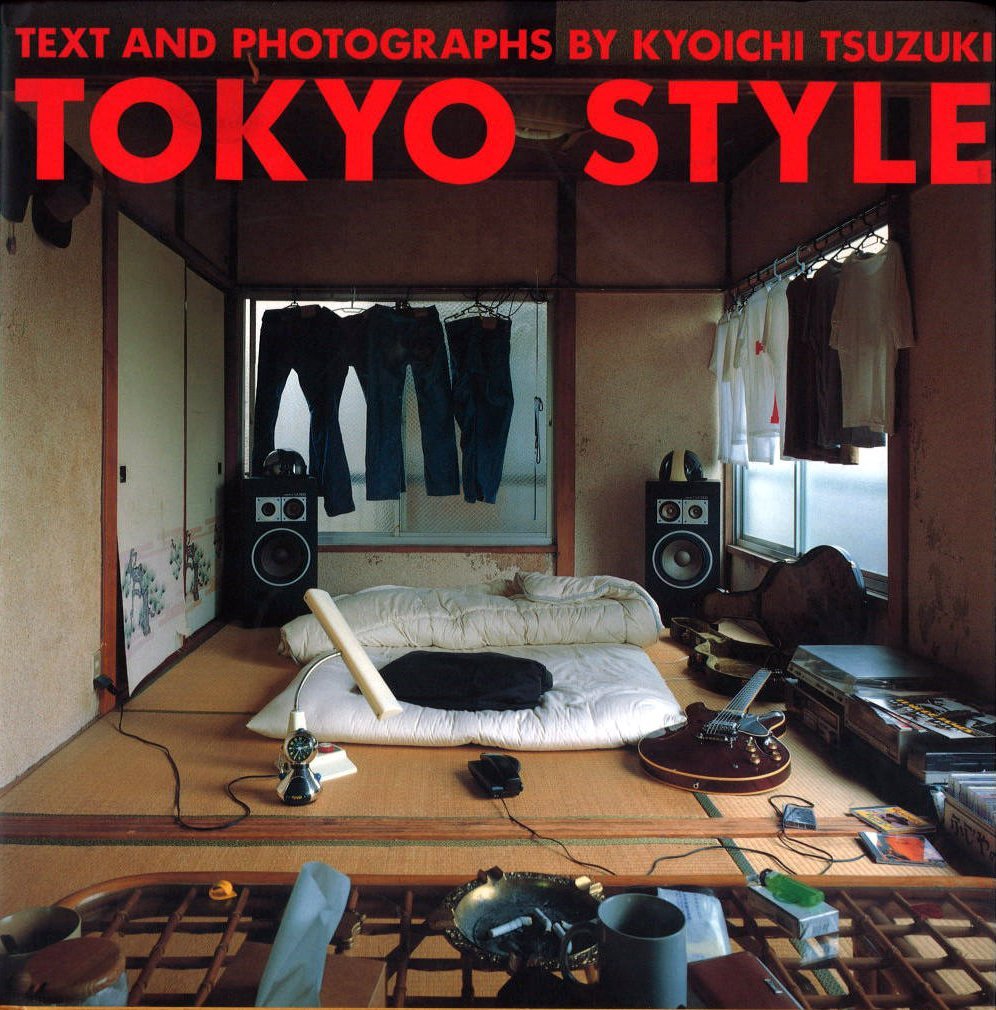

Tokyo Style

The following texts and photographs have been taken from Kyoichi Tsuzuki’s book,

Tokyo Style (Kyoto Shoin Co., Ltd, 1993).

Word has it that Tokyo is the hardest city in the world to live in. $10 cups of coffee, $100 per head dinners, $100,000 per square meter land prices … but for us Japanese, the stories you hear have almost no reality. Any more than the notion of coming home from work to find the wife in a kimono bowing at the entryway, the subtle pinewind whistling of a tea ceremony kettle in the background. […] Let me tell you: our lifestyles are a lot more ordinary. We live in homely woodframe apartments or mini-condos crammed to the gills with things. Formica-topped kotatsu heater-tables plunked down on throwrugs. Western furniture sitting right on top of the tatami mats. It’s what we find comfortable. […] Sure, for the same amount of money, we could rent much larger places way out in the burbs. And yet we consciously opt for living in tiny cubbyholes right in the heart of the city … Well, first of all, Tokyo is a safe city […] So if that’s the case, why not get yourself a one-room pad close by your favorite bookstores and boutiques and restaurants and watering holes? You can just use your neighborhood as your extended living room. At least in this city, there’s plenty of happy folks who think that that’s really the life! Bookstore shelves are lined with more publications on ‘Japanese space’ than you’d ever want to see … But how many of these places look lived in? That’s because what these books show are the co-creations of known architects and photographers, or else very skillful presentations of designer products. It’s because no one can live like those pictures that they make attractive showpieces. […] On the other hand, I know a lot of people who manage to live in cluttered closet-sized walk-ups with great ease and style. And yes, I do mean style. By definition, a ‘style’ is something you can see catching on among different people; whereas if you can’t find one person around you living the other way, it can hardly be considered a ‘style.’ […] Hence this book: I wanted to show you the real Tokyo Style, the places we honest-and-truly do spend our days. […] Still, if world economic trends continue to spiral downward, there’s going to be a lot more people living in a lot tighter spaces. Who knows? This art of living well in small quarters might just prove to be the style of the future.

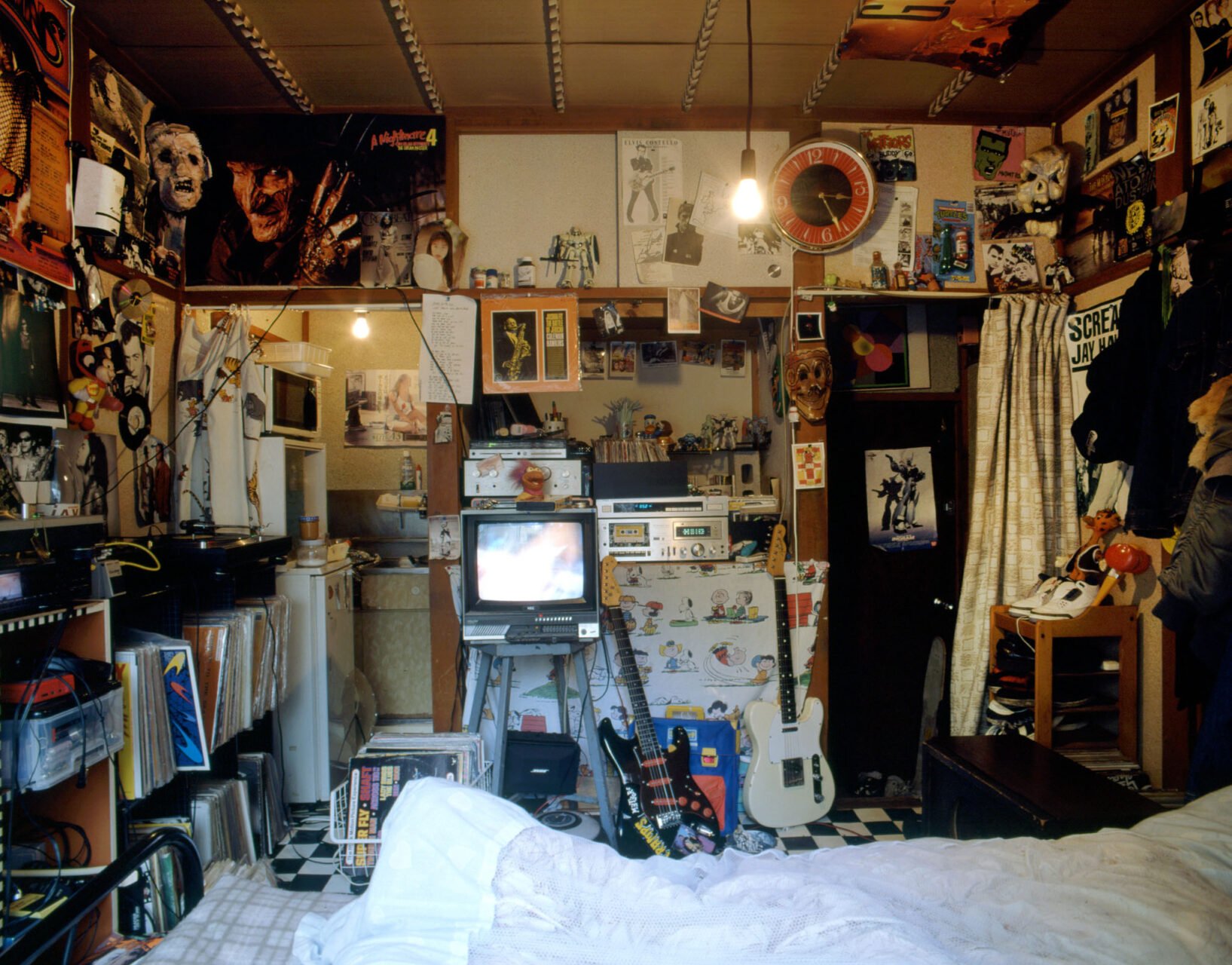

Hommage to how-much-to-the-square A three-tatami-mat one-room where lives this DJ trainee. While he has, of course, neither private bath or toilet, the Y27,000 monthly rent and walking distance to gigs in Shinjuku are certainly attractive. He uses this room to make record selections, record tapes and practice musical instruments. The room is wholly lacking in storage space, so he makes maximum use of all floor, wall and ceiling space to display his possessions. Living on a time schedule completely opposite of most people, he relies on a pocket beeper instead of a telephone. When paged, he can rush to a nearby public phone—or just forget it if he doesn’t feel like it. Either way, it’s a cheap solution.

Ordinary is best A graphic designer, his wife and two daughters live in this typical traditional-style house in the suburbs of Tokyo, a two-hour commute to his office—not unusual for the Tokyo suburbanite. He inherited this house with its small garden from his father more than twenty years ago and has been living here ever since, with no major changes in the interiors. Most weeknights, he gets home very late from work, so the house typically belongs to ‘the girls’. After the tension of his ‘ultra-clean hard-edge design world’, however, he feels much more comfortable here in this warm, homey clutter.

An artistic cohabitation Two Kyoto-born brothers—thirty-two and thirty-three respectively—have been living in this old, wooden two-room apartment for more than eight years, ever since art school. Though old and un-soundproofed, US $600 per month for two rooms, a kitchen, separate toilet and bath is quite reasonable for Tokyo standards. One room, the entryway in the corner beside the bed, is occupied by the elder brother. The younger brother sleeps beside the kotatsu—a low table with heating unit on the underside—which leaves only a foot-wide space to the wall. Overflowing with CDs and books, the place keeps them happy because they both have their own small studio spaces. The only problem is that they have to use headphones to listen to music late at night and cannot use amplifiers for practicing electric guitars.

Collage living Workroom-cum-living quarters for a junk artist, who has just embarked upon color copy art, so now there’s a huge copying machine and stacks of paper everywhere. It’s less and less possible to even move around here. The veranda has been converted into a junk stockpile and you can no longer even open the door. And the drawn blinds—he works at night—add to the claustrophobic effect. Only the large bathroom provides some sense of relief.

Home sweet home Another free ’n easy Japanese ‘new family’—the wife who loved cute cartoon character goods so much she went to work for a company that produces them, her husband whom she met while touring, and their baby. They live upstairs from her folks, making it a two-generation household, but except for meals the three of them generally keep to themselves. Everything from the furnishings to the lunch box he takes to work each day are character goods—not your average brand loyalty here! She says it took a good number of years to lay in such an impressive way.

Play it as it lays After graduating high school, this 18-year-old boy musician-wannabe decided to come to Tokyo. Packing his belongings on his small motorcycle, he rode all the way up from Nagasaki to Tokyo, more than a week’s trek. Looking for somewhere with a bit of nature around, like back in Nagasaki, he found an apartment near the Tama River Boat Racing Centre. A peaceful suburban and part-agricultural environment most of the time, this area becomes extremely lively on weekends when thousands of gamblers converge on the races. Although he has formed a band with other transplanted Nagasaki boys, they have yet to earn any income from it, so he works on construction crews along with his fellow band members. The only furnishing in the apartment, a noisy commercial-use refrigerator, was found on a building site.

Toyko Style (Kyoto Shoin Co., Ltd, 1993).

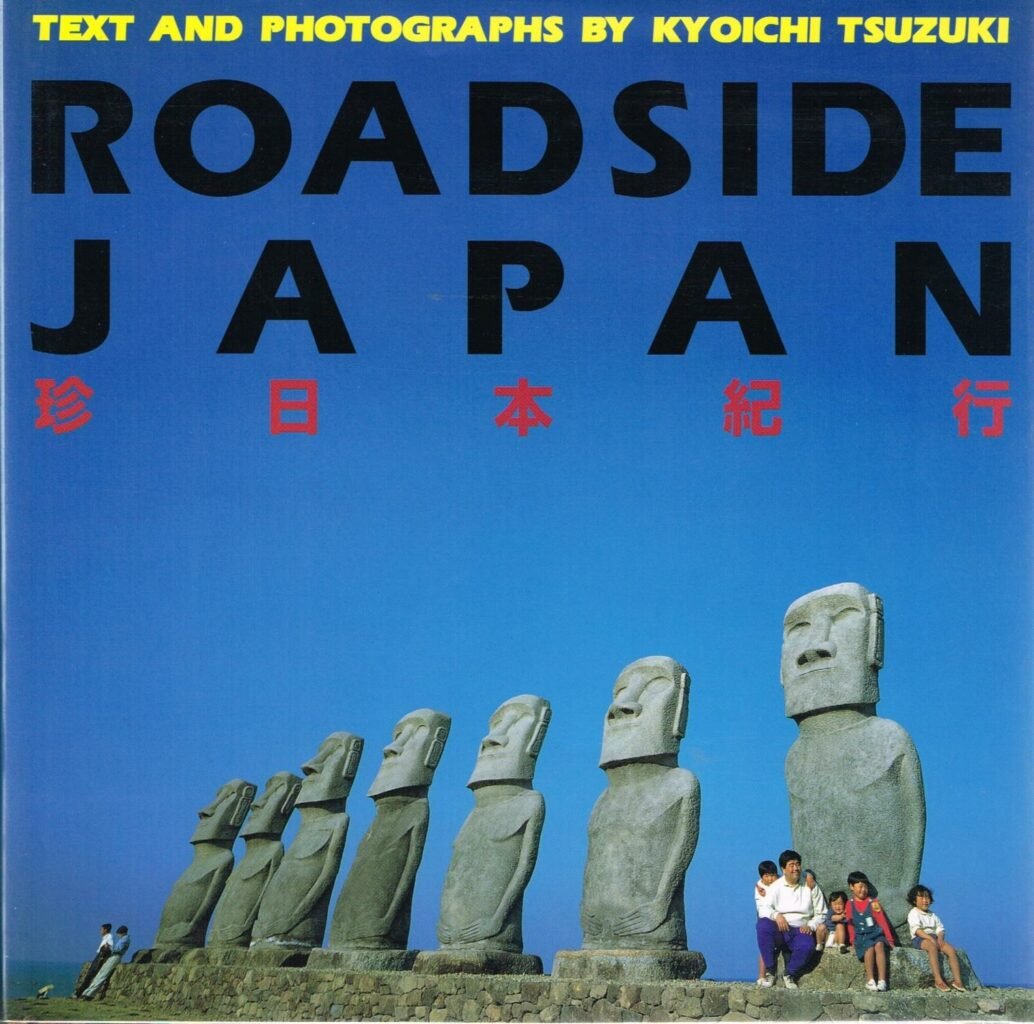

Roadside Japan (RAM Publications & Distribution, 1998).

Continue here for Kyoichi Tsuzuki’s original interview from Apartamento Issue #20, and grab yourself the latest release of the cult classic!